The Royal Game of Ur and how to Re-Create it

Games are perhaps the most natural way for us to learn in an active manner.

Attempting to re-create and design a game is a great task to challenge our mental and artistic creativity. Studying and then playing an ancient game is also a good way to practice the study of “living history”, thus focusing history not on kings and generals, but as a study of the life of ordinary people. In this activity, we are going to re-create the Royal Game of Ur, perhaps the most ancient board game we know of in history!

The Royal Game of Ur is an ancient is a two-player strategy board game that was invented in ancient Mesopotamia during the early third millennium BC. The game was popular across the Middle East and boards for playing it have been found also in Egypt, Crete and Sri Lanka. At the height of its popularity, the game acquired spiritual significance, and events in the game were believed to reflect a player’s future and convey messages from deities or other supernatural beings. Although it has disappeared for unknown reasons, the board game and pieces have been rediscovered and game historians (yes, that is a real job), think they have worked out how to play it.

Well now, let’s learn how to play and create the game!

Step 1 – The board

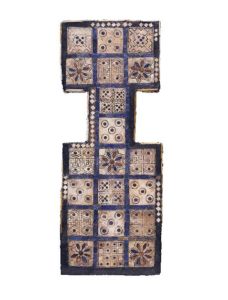

You will need to create this board:

There are 20 squares with different patterns. You can create your own patterns if you want, but they need to follow the same logic as in the original board.

Here is an example for the board that one of my students made:

Step 2 – The Game Pieces

For the game pieces, you will need to create (or use) two sets of six stones. Each set should be a different colour (each one of the two players will have six pieces).

Your stones should be small enough to fit in each of the twenty squares in the board.

This is how the British Museum re-created the pieces – can you think of another way to do them?

Step 3 – “Ancient Dice”

You might be surprised, but it took a long time for people to come up with the invention of the dice that we have today. So what did the Mesopotamians do?

Well, they uses pyramid-like stones. They would make a dot on one side of the stone, and then throw four such stones. Each stone that landed with the dot faced up, counts as “1”. Since there are four stones, you can get anywhere between “0” (if all four stones falls on a side without a dot) and “4” (if all the stones fall with the dotted-side facing up). You probably do not have pyramid-shaped stones at home. So you need to think how you can create something else instead (for example, make one out of clay).

A “pyramid dice” looks like this:

This might be the hardest part at first. However, if you think about it, and use your knowledge of percentages, it can much easier.

The orginal “dice” has four edges, with one “dotted” edge, and an equal chance to fall on each edge. So, we just need to create something that has a one-in-a-four-chance, or 25%, of something coming up.

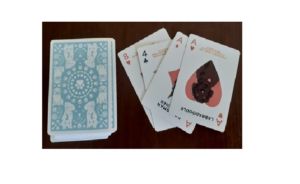

I, for example, use a normal deck of cards. Instead of throwing four “dices”, I draw four cards, and each “heart” symbol is “1”.

Can you find another way to create the “dice” or an alternative to it?

Lastly, here are the full instructions to the game so that you can play it at home with your family. Have Fun!

Here I drew two “heart” cards, so that is equal to “two”!

Instructions – How to Play the Game

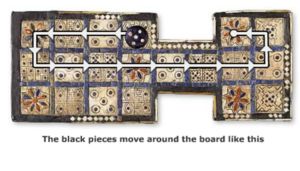

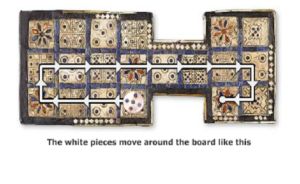

The goal of the game is to move all your pieces to the other side of the board before the other player does. All the pieces start outside of the board, and each player can move one piece in their turn. This is how each player can move their pieces:

A few more rules:

- On your turn, you can decide after you threw the dices, which of your pieces to move on the board, or to enter a new piece on to the board.

- You may not put two pieces of your pieces on the same square

- If your piece lands on a square with a piece of your rival, you “kick home” your rival’s piece! (it needs to start again from outside the board).

- If there is no place for you to move any of your pieces, you lose that turn.

- You can only finish the journey of a piece with the exact number in the dices/stones. For example, if you have a piece that is two squares from the “ending” rosette square, and you role a “three”, then you cannot move that piece.

There are 5 rosette squares.

If you land on a rosette square you get another throw of the dice and your piece is safe from a rival’s attack.

Bonus challenge:

There are other interesting squares on the board except the “rosette” squares. Can you make up an additional rule involving one of them?

For example, we thought that the square with five dots could mean on your next turn throw five dices instead of just four. What rules can you think of?